Electroacoustic music + dogs

Currently, I’m dog-sitting my mom’s two little dogs — Annie, a senior dachshund mix, and Ludi (Ludwig van Beethoven), a 9-month-old dachshund puppy. Combine them with my two little mutts and you’ve got a pile o’ dogs. Ludi is still very much a puppy, which makes it a bit difficult to spend time in the studio, where there’s no way I’ll be able to pay attention to what he’s doing. I fear for all the things (cords! guitars! subwoofer! bins of cables!). In fact, during the writing of this post, his behavior caused me need to search “stimming for dogs,” which should tell you something.

So today will be for writing in various forms: blog post(s), and working on a minimum viable score for my upcoming show in Chicago with my lovely friend Henna Chou. Here’s the blurb about what we’re doing:

Alison Wilder (electronics) + Henna Chou (cello), reuniting after 20 years of long-distance musical friendship, will premiere “On Sand,” a 3-movement improvisational electroacoustic work that asks questions like “what if we rejected language after it hurt us the first time?” and “how can we remember and tell stories without bodies?”

For my part, I’ve been working on crafting a setup that will allow for about 40 minutes of improvisational music that Henna and I can create in real time together. Although we’ve been long distance friends for 15 or 20 years, to the best of either of our memories, we’ve never played music together before. (Well, short of a hedonistic moving drum circle that spontaneously occurred very late at night after a transcendent show where both of our bands opened for a really great Swedish band. If I’m recalling correctly, which I absolutely may not be.)

Because I am who I am, and putting together sound worlds is kind of my thang, I’ve been working to create a series of sound worlds that we can live in for those 40 minutes. Difficulty level: I want to actually perform music instead of button-pushing. Challenging! Although it would be easiest to throw some droney pads and weird samplers into Ableton and call it a day, I’m attempting a more songwriterly/composerly approach to the piece. That means that, instead of just showing up and jamming, I’m putting in some serious effort.

Last time I played a full-on improvisational/noise/experimental show was…we’ll just say “awhile back.” And “showing up and jamming” is a pretty apt description of the approach I took to these sorts of shows back then! 🙂

The date on the photos says 2009, which…maaaybe is correct? I performed John Zorn’s Cobra with a big, fun group led by Dan Blacksberg at the Rotunda, a delightful community arts space in West Philly. In those days, I wouldn’t have dreamed of using a computer to do a show like this. That said, this was a minimal setup for me — a Nord Electro and a couple of pedals.

This Cobra show is coming up for me at the moment because, in my memory, it’s emblematic of modern experimental improvisational music: it was an absolute blast to perform, sometimes even felt transcendent, but I don’t think it could stand the re-listening test. Meaning, when you listen back to a recording, that transcendence is gone, and the music is either boring, or muddled, or pure chaos, or has fleeting moments of music surrounded by not-really-music. (To be fair, I don’t have a recording of this performance and am relying my memory. Maybe it really was music, all the way through.)

So, as you may have guessed by now, I have complicated feelings about modern improvisational music. On the one hand, conceptually, I find it to be extremely compelling, for all the reasons improvising is GREAT. On the other hand, it almost always falls short for me, musically. Please note that this is 100% personal and not a reflection on the (stupid and useless) question of “What Is Objectively Good Music?”

Pierre Schaeffer, my favorite musique concrète composer, wrote that he never felt like he reached his goal of making actual music with found sound. His statement is complicated by his historical position in the world of 20th-century European art music, but given that my training took place in that world too, I understand what he meant. Music can provide a unique and glorious sense of mental play. But making that happen generally isn’t easy, even using tools that are meant to do it (tools like organs and…shudder…saxophones). Trying to make it happen with bits of environmental sound is almost impossible.

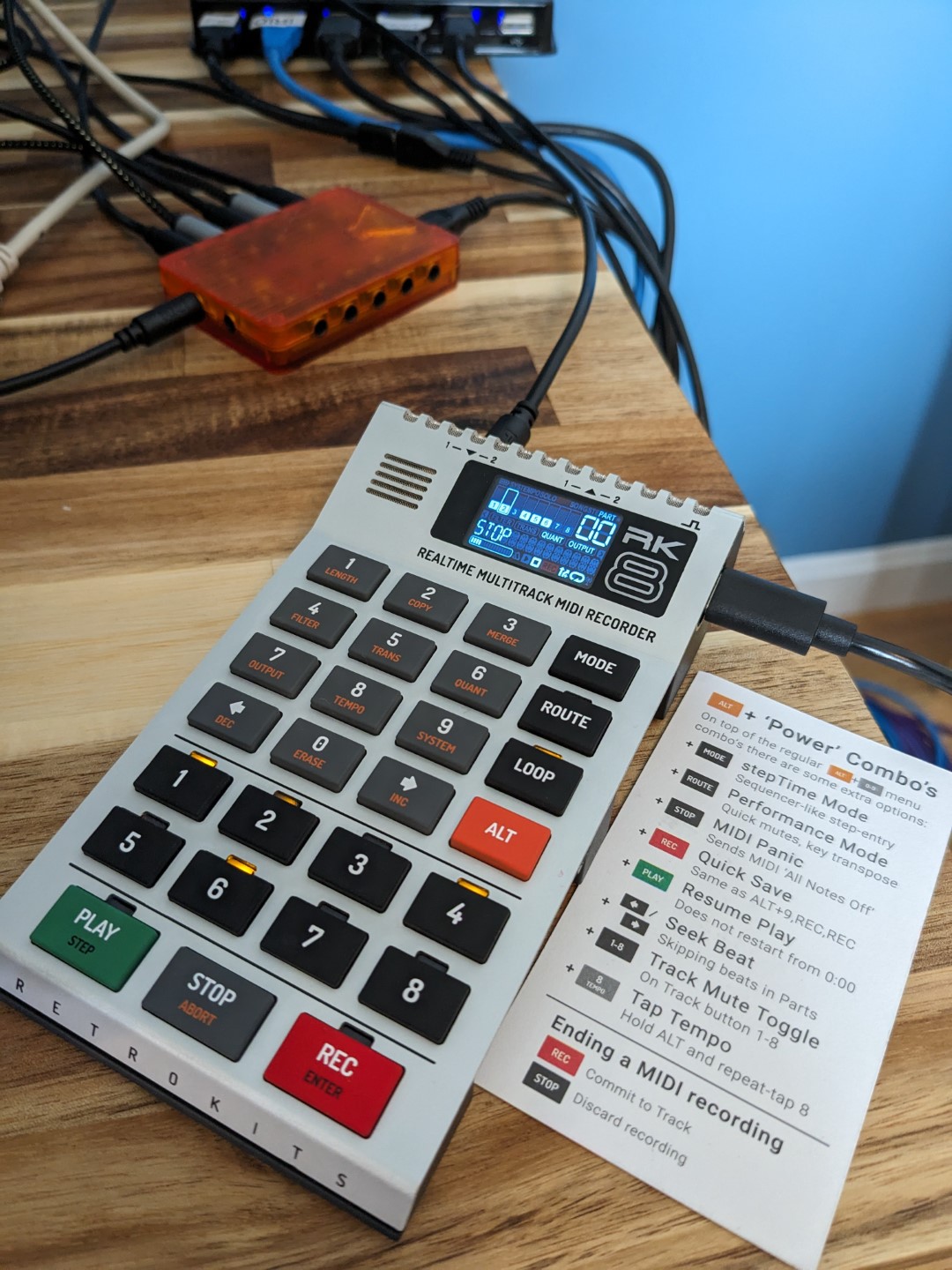

Of course, the piece I’m working on to perform with Henna has the advantage of modern computing. Take that, Pierre! I’m using Ableton with a Push controller and creating a project that allows me to treat the session like one big instrument…no pre-recorded sequences allowed. I’m using some bits of pre-recorded music, but I’m using them more like found sound to be woven with, not as a complete tapestry unto themselves. (Sorry for the gooey poetic language, I can’t think of less pretentious-sounding way to say it at the moment.)

I’m also using a couple of soft synths and/or Max patches, possibly sometimes controlled by an EWI, depending on whether I have time to work it in. I’m wishing for my hardware synths every time I work on the piece, but I’m definitely not taking any synths on the plane this time.

I’m super grateful that Henna asked me to do this show, because preparing for it has forced my hand in terms of figuring out a way to perform live in a way that satisfies my current musical inclinations. While I’m probably not mostly going to perform in the experimental/improvisational music setting (although who knows!), the tools and methods I’m coming up with for this show are almost completely transferable to the sorts of music I make as Blix Byrd, and with Doctor Body.

So once this Chicago show is wrapped, I’ve decided that, instead of taking all the material I’ve started for the next Blix Byrd release directly into the studio, I’m going to work it up as a live show first. This is a direction I’ve wanted to go in for awhile, and I’ve worked hard to make my studio/life ready for this sort of approach, so I’m thrilled to see a path to do it

So if you’re reading this and want a Blix Byrd and/or Doctor Body show in, say, six months, hit me up. Hopefully I won’t have to take any mother fucking synths on any mother fucking planes.